Zero Knowledge Proof: FRI-based Polynomial Commitments and Fiat-Shamir

Table of Contents

From older posts, we have seen various types of polynomial commitment scheme (PCS) and interactive oracle proof (IOP), which are important ingredients for building SNARK for general circuits. Today, we will talk about FRI - another polynomial commitment scheme based on Reed-Solomon code, and revisiting Fiat-Shamir Transformation.

Resource

Round-by-round Soundness, Fiat-Shamir, and Sum-check

Detail

Recall

Polynomial-IOP

Let’s talk about a special case of a polynomial IOP that suffices for most but not all SNARKs. In this case, $P$’s first message, who is the prover, to the verifier $V$ specifies a polynomial $h$.

The problem here is that $h$ has big description size, as large as the circuit, so if $P$ send full polynomial, it will destroy succinct ability of SNARK, so $V$ does not learn $h$ in full.

To deal with the problem above, V is permitted to evaluate $h$ at one point, and after that, $P$ and $V$ execute a standard interactive proof, meaning that every other message from $P$ is short and read by $V$ in full. At the end of protocol, $V$ decides accept or reject.

Polynomial Commitment Scheme

Polynomial Commitment Scheme (PCS) is a cryptographic protocol that can turn a polynomial IOP into a succinct interactive argument. The high-level idea of PCS is:

- $P$ binds itself to a polynomial $h$ by sending a short string $Com(h)$, this will ensure succinct ability.

- $V$ can choose $x$ and ask $P$ to evaluate $h(x)$.

- After received $x$, $P$ sends $y$, which is supposed to be an evaluation, plus a proof $\pi$ that $y$ is consistent with $Com(h)$ and $x$.

There are two important things that PCS needs to have:

- $P$ cannot produce a convincing proof for an incorrect evaluation.

- $Com(h)$ and $\pi$ are short and easy to generate, and proof $\pi$ is easy to check.

A Zoo of SNARKs

As I said in the start of this post, there are several different polynomial commitments and several different polynomial IOPs. We can mix-and-match to get different tradeoffs between $P$ time, proof size, setup assumptions, etc. Notice that transparency and plausible post-quantum security determined entirely by the polynomial commitment scheme used.

From what we learned, we can categorize poly-IOPs into three classes:

- Based on interactive proofs (IPs)

- Based on multi-prover interactive proofs (MIPs)

- Based on constant-round polynomial IOPs

Roughly speaking, the above SNARKs are listed in increasing order of prover costs but decreasing order of verification costs. So SNARKs based on IP have the fastest prover, but higher verification costs than SNARKs like Marlin and PlonK.

We can also categorize polynomial commitment scheme into three classes, which is described in this table below:

| Based on | Transparent | Post-quantum | Homomorphic | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairings + trusted setup | No | No | Yes | KZG10 |

| Discrete logarithm | Yes | No | Yes | IPA/Bulletproofs, Hyrax, Dory |

| IOPs + hashing | Yes | Yes | No | FRI, Ligero, Brakedown, Orion |

Notice that classes 1 and 2 are homomorphic, which lead to efficient batching/amortization of $P$ and $V$ costs.

Some specimens from the zoo

Transparent SNARKS

1. [Any polynomial IOP] + IPA/Bulletproofs polynomial commitment.

Ex: Halo2-ZCash

Pros: Shortest proofs among transparent SNARKs.

Cons: The verifier is very slow.

2. [Any polynomial IOP] + FRI.

Ex: STARKs, Fractal, Aurora, Virgo, Ligero++

Pros: Shortest proofs amongst plausibly post-quantum SNARKs.

Cons: Proofs are large, about 100s of KBs depending on security.

3. MIPs and IPs + [fast-prover polynomial commitments].

Ex: Spartan, Brakedown, Orion, Orion+(a part of a paper called HyperPlonk)

Pros: Fastest $P$ in the literature, plausibly post-quantum + transparent if polynomial commitment is.

Cons: Bigger proofs than 1. and 2. above.

Non-transparent SNARKS

1. Linear-PCP based.

Ex: Groth16 (We will learn about it in next post)

Pros: Shortest proofs with 3 group elements with handful of pairing operation for verifier

Cons: Circuit-specific trusted setup, slow and space-intensive $P$, not post-quantum

2. Constant-round polynomial IOP + KZG polynomial commitment

Ex: Marlin-KZG, PlonK-KZG

Pros: Universal trusted setup

Cons: Proofs are ~4x-6x larger than Groth16, $P$ is slower than Groth16, and not post-quantum

- A counterpoint in terms of prover time is that Groth16 is somewhat restricted in the kinds of circuits it can use, but Marlin and PlonK can use more flexible intermediate representations than circuits and R1CS.

FRI (Univariate) Polynomial Commitments

Recall: Univariate Polynomial Commitments

Let $q(x)$ be a degree-($k - 1$) polynomial over field $\mathbb{F}_p$, for example, $k = 5$ and $q(X) = 1 + 2X + 4X^2 + X^4$.

The prover want to succinctly commit to $q$, and later reveal $q(r)$ for an input $r$ chosen by the verifier. After that, the verifier going to prove that the returned evaluation is indeed consistent with the committed polynomial.

In the previous post, we know that $P$ can Merkle-commits to all evaluations of the polynomial $q$, and when $V$ requests $q(r)$, $P$ reveals the associated leaf along with opening information. But there are two problems with this approach:

- The number of leaves is $|\mathbb{F}|$, which means the time to compute the commitment is at least $|\mathbb{F}|$. So when working over large fields likes $|\mathbb{F}| \approx 2^{64}$ or $|\mathbb{F}| \approx 2^{128}$, computed time will be very long, which is a big problem.

- The verifier does not know if $f$ has degree at most $k$.

We will discover how to fix above problems, which are used to build FRI.

Fixing the first problem

- Rather than $P$ Merkle-commiting to all $p - 1$ evaluations of $q$, $P$ only Merkle-commits to evaluations $q(x)$ for those $x$ in a carefully chosen subset $\Omega$ of $\mathbb{F}_p$.

- $\Omega$ has size $\rho^{-1}k$ for some constant $\rho \le 1/2$, where $k$ is the degree of $\rho$. $\rho$ is called the “rate of the Reed-Solomon code” used, and is called the “FRI blowup factor” when $\rho^{-1} \ge 2$.

- There is a strong tension between $P$ time and verification costs: The bigger the blowup factor, the slower $P$ is, because it has to evaluate $q$ on more inputs and Merkle-hash the results. Proof length will be about $(\lambda/log(\rho^{-1})) * log^2(k)$ hash values, which $\lambda$ is the security parameter a.k.a “$\lambda$ bits of security”. We can think of $\lambda$ as roughly the logarithm of the amount of work that a cheating prover would have to do to convince the verifier to accept a false claim in FRI.

More specifically about subset

- Let $n = \rho^{-1} k$. Assume $n$ is a power of $2$, then the key subset $\Omega$ comprises all $n$-th roots of unity in $\mathbb{F}_p$.

Remember that $x$ is a $n$-th root of unity if $x^n = 1$.

If $\omega \in \mathbb{F}_p$ be a primitive nth root of unity, then $\Omega = {1, \omega, \omega^2, …, \omega^{n - 1}}$. Moreover, $\Omega$ is a multiplicative subgroup of $\mathbb{F}_p$.

We notice that $\Omega$ has size $n$ if and only if $n$ divides $p - 1$. We can use abstract algebra to prove it. This is why many FRI-based SNARKs work over fields like $\mathbb{F}_p$ with $p = 2^{64} - 2^{32} + 1$, therefore, running FRI over that field can support any power-of-two value of $n$ up to $|\Omega| = 2^{32}$ ($p - 1$ is divisible by $2^{32}$).

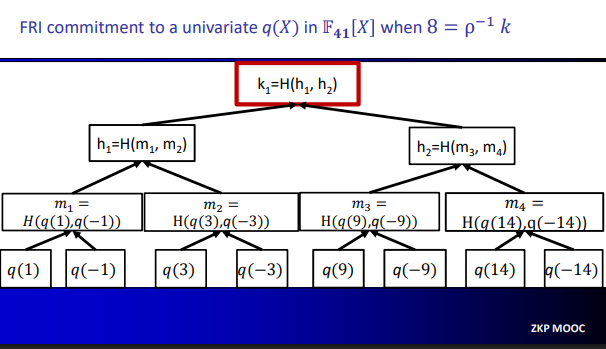

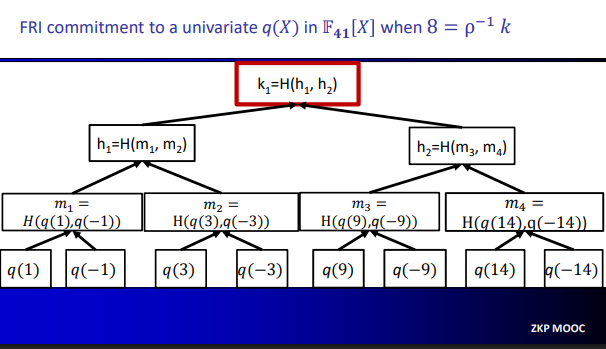

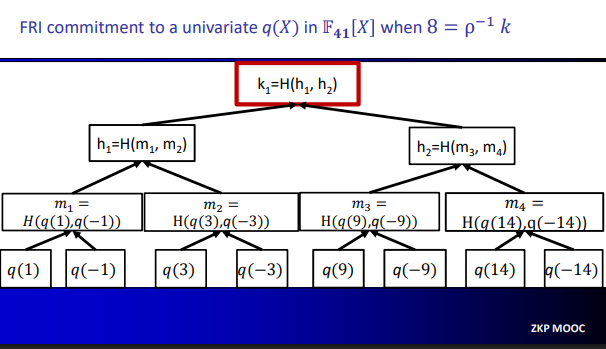

Example: FRI commitment to a univariate $q(X)$ in $\mathbb{F}_{41}[X]$ when $8 = \rho^{-1}k$

- We have $8$ is the biggest power of two that is a divisor of $p - 1 = 40$. And we have all 8-th roots of unity of $F_{41}$ are ${1, -1, 3, -3, 9, -9, 14, -14}$. With these informations, we can construct the Merkle Tree like this:

Fixing the second problem

- The verifier $V$ needs to know that the committed vector is all evaluations over domain $\Omega$ of some degree-($k - 1$) polynomial.

- Consider an idea from the probabilistically checkable proof: $V$ “inspects” only a few entries of the vector to “get a sense” of whether it is low-degree. More specifically, each query will add a Merkle-authentication path to the proof, which will generate $\log (n)$ hash values.

- Turn out, that idea is impractical, because $V$ would unfortunately have to inspect a large number of entries of the committed vector, and the field one would have to work over would be enormous.

- Instead, the FRI low-degree test will be interactive and consist two phases: Folding Phase and Query Phase.

Folding Phase

The prover need to repeatly do the following:

“Randomly fold the committed vector in half” - This mean pair up entries of the committed vector, have $V$ pick a random field element $r$, and use $r$ to “randomly combine” every two paired up entries, this work halves the length of the vector.

Have Prover Merkle-commit to the folded vector.

- The random combining technique is chosen so that the folded vector will have half the degree of the original vector

- The prover need to repeat the folding untill the degree should fall to $0$. At this point, the length of the folded vector is still $\rho^{-1} \ge 2$. But since the degree should be $0$, Prover can specify the folded vector with a single field element.

Here is an example of this phase in $\mathbb{F}_{41}$ and $8 = 4 * \rho^{-1}$

Query Phase

Prover $P$ may have “lied” at some step of the folding phase, by not performing the fold correctly, for example, sending a vector that is not the prescribed folding of the previous vector, or to “artificially” reduce the degree of the (claimed) folded vector.

Therefore, verifier $V$ attempts to “detect” such inconsistencies during the query phase.

Query phase: $V$ picks about $(\lambda/\log (p^{-1})))$ entries of each folded vector and confirming each is the prescribed linear combination of the relevant two entries of the previous vector. The proof length is roughly $(\lambda/\log (\rho^{-1})) \log (k)^2$ hash evaluations.

Folding Phase: more detail

Let’s talk about Folding Phase in a mathematical way: Suppose we need to commit a polynomial $q(X)$, then the Folding Phase does:

- Split $q(X)$ into “even and odd parts” in the following sense: $$q(X) = q_e(X^2) + X * q_o(X^2)$$ and note that both $q_e$ and $q_o$ have (at most) half the degree of $q$.

An example: if $q(X) = 1 + 3X + 3X^2 + 7X^3$, then $q_e(X) = 1 + 3X$ and $q_o(X) = 2 + 4X$

$V$ picks a random field element $r$ and sends $r$ to $P$.

The prescribed “folding” $q$ is $q_{fold}(Z) = q_e(Z) + rq_o(Z)$

Clearly $deg(q_{fold})$ is hald the degree of $q$ itself.

Let’s back to an example in $\mathbb{F}_{41}[X]$ and explain what happen in this picture.

Fact: Let $x$ and $-x$ be $n$-th roots of unity and $z = x^2$, then $$q_{fold}(z) = \frac{r + x}{2x}q(x) + \frac{r - x}{-2x}q(-x)$$

To prove the statement above, note that $q(x) = q_e(z) + xq_o(z)$, so if $r = x$ then $q_{fold}(z) = q(x)$ and $q_{fold}(z) = q(-x)$ if $r = -x$ otherwise. The fact follows because it gives a degree-1 function of $r$ with exactly this behavior at $r = x$ and $r = -x$.

Another fact is that the map $x \mapsto x^2$ is 2-to-1 on $\Omega = { 1, \omega, \omega^2,…,\omega^{n - 1}}$ ensures that the relevant domain halves in size with each fold. Other domains like ${0, 1,..,n-1}$ don’t have this property.

Compare to Lecture 7

- In lecture 7, we have covered a variety of polynomial commitments (Ligero, Brakedown, Orion) that are similar to FRI.

- All use error-correcting codes.

- The only cryptography used is hashing (Merkle-hashing + Fiat-Shamir)

- All schemes in last lecture viewed a degree-$d$ polynomial as $d^{1/2}$ vectors each of length about $d^{1/2}$ and performed a single random fold on all these vectors.

- This resulted in larger proofs (size roughly $d^{1/2}$), but have some advantages like linear-time prover or field-agnostic.

- Proof size can be reduced via SNARK composition.

- FRI views a degree-$d$ polynomial as a single vector of length $\mathbb{O}(d)$ and “randomly folds it in half” logarithmically many times.

Security Analysis of FRI

Recall that at the start of the FRI polynomial commitment, $P$ Merkle-commits to a vector $w$ claimed to equal $q$’s evaluations over $\Omega$.

- $\Omega$ is the set of $n$-th roots of unity in $\mathbb{F}_p$, where $n = \rho^{-1} k$.

- $q$ is claimed to have degree less than $k$.

Let $\delta$ be the “relative Hamming distance” of $q$ from the closest polynomial $h$ of degree $k - 1$. $\delta$ is the fraction of $x \in \Omega$ such that $h(x) \ne q(x)$. Then we have a result:

$P$ “passes” all $t$ “FRI verifier queries” with probability at most $\frac{k}{p} + (1 - \delta)^t$ The proof of that result can be watched in lecture video.

The Known Attack on FRI

- Recall that at the start of the FRI polynomial commitment, $P$ Merkle-commits to a vector $w$ claimed to equal $q$’s evaluations over $\Omega$.

- Here, $\Omega$ is the set of $n$-th roots of unity in $\mathbb{F}_p$, where $n = \rho^{-1}k$, and $q$ is claimed to have degree less than $k$.

- The following prover $P$ strategy works for any $q$ (even ones maximally far from degree $k$) and passes all FRI verifier checks with probability $\rho^t$.

- $P$ picks a set $T$ of $k = \rho n$ elements of $\Omega$ and computes a polynomial $s$ of degree $k - 1$ that agrees with $q$ at those points, then folds $s$ rather than $q$ during the folding phase.

- And therefore, all $t$ verifier queries lie in $T$ with probability $\rho^t$.

Polynomial Commitment from FRI

An attempt

- $P$ Merkle-commits to all evaluations of the polynomial $q$.

- When $V$ request $q(r)$, $P$ reveals the associated leaf along with opening information.

- When using the idea above, we have some problems with FRI:

- $P$ has only Merkle-committed to evaluations of $q$ over domain $\Omega$, not the whole field. This in an issure because $V$ may request an evaluation of $q$ at any point $r$ in the field, therefore, it’s not to be enough for the prover to simply reveal some leaf of the Merkle tree along with authentication.

- $V$ only knows that $q$ is “not too far” from low-degree, not exactly low-degree. It means that the verifier is convinced that the relative Hamming distance of $q$ from a degree $k - 1$ polynomial is not too big after FRI low-degree test, but does not know that relative Hamming distance is zero.

=> We need a way to fix these problems above to have a Polynomial Commitment Scheme from FRI.

A fix for both problems

- Recall the following fact used in KZG commitments:

- Fact: For any degree-$d$ univariate polynomial $q$, the assertion $q(r) = v$ is equivalent to the existence of a polynomial $w$ of degree at most $d$ such that $q(X) - v = w(X)(X - r)$.

- So to confirm that $q(r) = v$, $V$ applies FRI’s fold/query procedure to the function $(q(X) - v)(X - r)^{-1}$ using degree bound $d - 1$, then whenever the FRI verifier queries this function at a point in $\Omega$, the evaluation can be obtained with one query to $q$ at the same point.

- It’s not difficult to show that in order for the prover to pass the verifier’s checks in this polynomial commitment with noticeable probability. $v$ has to equal $h(r)$, where $h$ is the degree-$d$ polynomial that is closest to $q$.

- A caveat here is that the security analysis requires $\delta$ to be (at most) $(1 - \rho)/2$. Each FRI verifier queries brings (less than) 1 bit of security, not $\log 2(1/\rho)$ bits.

- People are using FRI today as a weaker primitive than a polynomial commitment, which still suffices for SNARK security. A list of polynomial commitment scheme effectively does not bind $P$ to a single low-degree polynomial as required by a polynomial commitment scheme, but instead bounds $P$ to a small set of low-degree polynomials. With effective polynomial commitment scheme, prover is able to choose any low-degree polynomial $h$ from the small set and answer $h(r)$.

The Fiat-Shamir Transformation and Concrete Security

You can notice that Fiat-Shamir transformation is appeared many times in this ZKP series, when we need to remove the “interaction” part. Fiat-Shamir is used in almost all SNARKs with the notable exception of Groth16. So let discuss Fiat-Shamir in more detail.

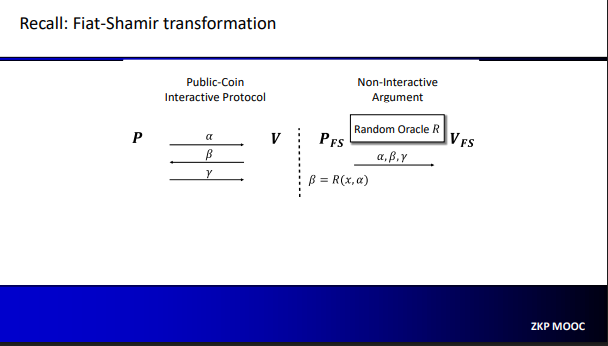

Recall

In the interactive protocol, we have three steps:

- $P$ send message $\alpha$ to $V$

- $V$ send random challenge $\beta$

- and $P$ responds with message $\gamma$

When applying Fiat-Shamir, we replace $\beta$ with a hash evaluation $R$ with the cryptograpic hash function modeled as a random oracle $R$. In the picture above, $\beta = H(x, \gamma)$.

There are many critical vulnerabilities in real-life ZK implementation start from misimplementation of Fiat-Shamir Transformation. I suggest reading this paper to have an overview of these bugs and avoid it.

An unfamiliar attack on Fiat-Shamir is Grinding attack, where prover iterates over first-messages $\alpha$ until it finds one such that $R(x, \alpha)$ is “lucky”.

- For example, suppose you apply Fiat-Shamir to an interactive protocol with 80 bits of statistical security (soundness error $2^{-80}$), then with $2^b$ hash evaluations, grinding attack will succeed with probability $2^{-80 + b}$.

For a collision-resistant hash function (CRHF) configured to 80 bits of security, the fastest collision-finding procedure should be a birthday attack.

Interactive vs. Non-Interactive Security

Interactive Security

A polynomial commitment scheme such as FRI, when run interactively at “$\lambda$ bits of security”, has the following security guarantee:

- Assuming $P$ cannot find a collision in the hash function used to build Merkle trees, a lying $P$ cannot pass the verifier’s checks with probability better than $2^{-\lambda}$.

- A lying $P$ must actually interact with $V$ to learn $V$’s challenges, in order to find out if it receives a “lucky” challenge.

For example, if $\lambda = 60$, then with probability at least $1 - 2^{-30}$, $V$ will reject (at least) $2^{30}$ times before a lying $P$ succeeds in convincing $V$ to accept.

Non-Interactive Security

- Suppose Fiat-Shamir is applied to an interactive protocol such as FRI that was run at $\lambda$ bits of interactive security.

- The resulting non-interactive protocol has the following much weaker guarantee:

- A lying $P$ willing to perform $2^k$ hash evaluations can successfully attack the protocol with probability $2^{k - \lambda}$.

- A lying $P$ can attempt the attack “silently”: Unlike in the interactive case, $P$ can perform a “grinding attack” without interacting with $V$ until $P$ receives a lucky challenge.

- Higher security levels $\lambda$ are necessary in this setting.

- 60 bits of interactive security is fine in many context, where in non-interactive security is not okay unless the payoff of a successful attack is minimal.

Fiat-Shamir security loss for many-round protocols can be huge

- Consider the following (silly) interactive protocol for the empty language (i.e.,

$V$ should always reject).

- P sends a message (a nonce) which $V$ ignores.

- $V$ tosses a random coin, rejecting if it comes up heads and accepting if it comes up tails.

- The soundness error of this protocol is $1/2$. If you sequentially repeat it $\lambda$ times and accept only if every run accepts, the soundness error falls to $1/2^{\lambda}$

- Consider Fiat-Shamir-ing this $\lambda$-round protocol to render it non-interactive, then a cheating prover $P_{FS}$ can find a convincing “proof” for the non-interactive protocol with $\mathbb{O}(\lambda)$ hash evaluations with strategy:

- $P_{FS}$ grinds on the first repetition alone (i.e., iterate over nonces in the first repetition until one is found that hashes to tails. This requires 2 attempts in expectation until success.) Fix this first nonce $m_1$ for the remainder of the attack.

- Then $P_{FS}$ grinds on the second repetition alone until it finds an $m_2$ such that $(m_1, m_2)$ hashes to tails. Fix $m_2$ for the remainder of the attack.

- Then $P_{FS}$ grinds on the third repetition, and so on.

The takeaway

- Applying Fiat-Shamir to a many-round interactive protocol can lead to a huge loss in security, whereby the resulting non-interactive protocol is totally insecure.

- Fortunately, this security loss can be ruled out if the interactive protocol satisfies a stronger notion of soundness called round-by-round soundness.

- This means an attacker in the interactive protocol has to “get very lucky all at once” (in a single round)… it can’t succeed by getting “a little bit lucky many times”.

- The sequential repetition of soundness error $1/2$ is not round-by-round sound: The attacker can “get a little lucky” each round and succeed (i.e., in each round with probability $1/2$ it gets the “lucky” challenge Tails each round).

- The sum-check protocol is an example of a logarithmic-round protocol that is known to be round-by-round sound.

- Something analogous is known for Bulletproofs.

- FRI is a logarithmic-round interactive protocol that is always deployed noninteractively today. Note that it has not been shown to be round-by-round sound.

- SNARK designers applying Fiat-Shamir to interactive protocols with more than 3 messages should show that the protocol is round-by-round sound if they want to rule out a major security loss.