Zero Knowledge Proof: Polynomial Commitments based on Pairing and Discrete Log Problem

Table of Contents

In this post, we will learn deeply about polynomial commitment schemes based on Pairing and Discrete Logarithm Problem, mainly KZG, Bulletproofs and their variants.

Resources

A Zero-Knowledge Version of vSQL

Bulletproofs: Short Proofs for Confidential Transactions and More

Exploring Elliptic Curve Pairing - Vitalik Buterin

BLS12-381 For The Rest of Us - Ben Edgington

Poly-commits: Pairing & Discrete Log - Cryptonotes

Detail

Background

Group

A Group is a set $\mathbb{G}$ and an operation $*$ with these properties:

Closure: For all $a, b \in \mathbb{G}$, $a * b \in G$

Associativity: For all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{G}$, $(a * b) * c = a * (b * c)$

Identity: There exists a unique element $e \in \mathbb{G}$ such that for every $a \in \mathbb{G}$, $e * a = a * e = a$

Inverse: For each $a \in \mathbb{G}$, there exists $b \in \mathbb{G}$ such that $a * b = b * a = e$

For example, $\mathbb{Z}$ under addition, $\mathbb{F}_p$ under multiplication and elliptic curves are group

Generator

Generator is an element $g \in G$ that generates all elements in the group by taking all powers of $g$.

For example, with $\mathbb{Z}^*_7 = \lbrace 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 \rbrace$, $3$ is a generator, because $3^1 = 3, 3^2 = 2, 3^3 = 6, 3^4 = 4, 3^5 = 5, 3^6 = 1 \mod 7$.

Discrete Logarithm Assumption

Let $\mathbb{G}$ is a group with generator $g$, so we can represent $\mathbb{G} = \lbrace g, g^2,…,g^{p-1} \rbrace$. The discrete logarithm problem is, given $y \in \mathbb{G}$, we need to find $x$ such that $g^x = y$.

It turns out that this is very hard to do. There are some methods to solve this problem like Bruteforce, Baby-Step Giant-Step, Pohlig-Hellman, Smart’s attack,… but all of them need some special requirements, so people consensus that this problem is computationally hard.

Diffie-Hellman Assumption

Diffie-Hellman Key-Exchange is familiar with us, and that is based on the Diffie-Hellman Assumption, which is very similar to the discrete logarithm assumption: given $\mathbb{G}, g, g^x, g^y$, compute $g^{xy}$.

This is a stronger assumption than the discrete logarithm assumption. If someone can solve discrete logarithm problem, they can easily break this assumption by calculate $x$ from $g^x$ (or $y$ from $g^y$), then calculate $g^{xy}$.

This is also a hard problem and there is no efficient solution yet.

Bilinear pairing

Let’s talk about bilinear pairing. We have the following:

- $\mathbb{G}, \mathbb{G}_T$ are both multiplicative cyclic group of order $p$, where $\mathbb{G}$ is the base group with generator $g$, and $\mathbb{G}_T$ is the target group. Both $\mathbb{G}, \mathbb{G}_T$ have order $p$.

- $e$ is a pairing operation, it is the map $e: \mathbb{G} \times \mathbb{G} \to \mathbb{G}_T$.

We are interested with the bilinearity property: $$\forall P, Q \in \mathbb{G}: e(P^x, Q^y) = e(P, Q^y)^x = e(P^x, Q)^y = e(P, Q)^{xy}$$

Note that computing $e$ itself maybe efficient or not, depends on the groups that are being used; and also note that we can use two different base groups.

Example: Decisional Diffie-Hellman

Given $g^x$ and $g^y$, a pairing can check that some element $h = g^{xy}$ without knowing $x$ and $y$.

Example: BLS signature

BLS signature is a good example of using pairing. It’s a signature scheme with these functions:

- $keygen(p, \mathbb{G}, g, \mathbb{G}_T, e) \to (sk = x, pk = g^x)$ is the secret key and public key, respectively.

- $sign(sk, m) \to \sigma = H(m)^x$ where $H$ is a cryptographic hash function that maps the message space to $\mathbb{G}$.

- $verify(pk, \sigma, m) \to \lbrace 0, 1 \rbrace$ will verify if $e(H(m), g^x) = e(\sigma, g)$. Notice that $g^x$ comes to $pk$, and $H$ is a known public hash function.

KZG Polynomial Commitment Scheme

We discussed about KZG in previous post, but because we are talking about pairing, we will dig deeper about KZG Poly-commit Scheme.

Suppose you have a univariate polynomial function family $\mathcal{F} = \mathbb{F}_p^{\le d}[X]$ and a polynomial you would like to commit $f \in \mathcal{F}$. You also have a bilinear pairing $p, \mathbb{G}, q, \mathbb{G}_T, e$. Let see how KZG works with these.

$keygen(\lambda, \mathcal{F}) \to gp$

- Sample a random $\tau \in \mathbb{F}_p$

- Set $gp = (g, g^\tau, g^{\tau^2},…,g^{\tau^d})$

- Delete $\tau$. If it still exists now, malicious user can generate fake proofs. This is why a trusted setup is required for KZG.

$commit(gp, f) \to comm_f$

- The polynomial is represented with its coefficients $f(x) = f_0 + f_1x + f_2x^2 + … + f_dx^d$

- The commitment $comm_f = g^{f(\tau)}$. We don’t know $\tau$, but by $gp$, we can calculate $comm_f = g^{f_ 0 + f_1 \tau + f_2 \tau^2 + … + f_d \tau^d} = g^{f_0} \times (g^\tau)^{f_1} \times (g^{\tau^2})^{f_2} \times … \times (g^{\tau^d})^{f_d}$

$eval(gp, f, u) \to v, \pi$

- A verifier want to query this polynomial at point $u$, and you would like to show that $f(u) = v$ along with a proof $\pi$ that this is indeed true.

- We need to compute quotient polynomial $q(x)$ and $\pi = g^{q(\tau)}$ by using $gp$. $q(x)$ need to satisfy that $f(x) - f(u) = (x - u)q(x)$ and note that $u$ is a root of $f(x) - f(u)$.

$verify(gp, comm_f, u, v, \pi) \to \lbrace 0, 1 \rbrace$

- The idea is check the equation at point $\tau: g^{f(\tau) - f(u)} = g^{(\tau - u)q(\tau)}$ (1).

- But we only know $g^{\tau - u}$ and $g^{q(\tau)}$. By Diffie-Hellman assumption, calculate $g^{(\tau - u)q(\tau)}$ from $g^{\tau - u}$ and $g^{q(\tau)}$ is very hard. That’s where pairing need to!

- We can use pairing to calculate $e(comm_f/g^v, g)$ and $e(g^{\tau - u}, \pi)$ and check they are equal or not. If it’s equal, then we know (1) is correct because $e(g, g)^{f(\tau) - f(u)} = e(g, g)^{(\tau - u)q(\tau)}\iff f(x) - f(u) = (x - u)q(x)$ (assume that $e(g, g) \ne 0, 1$).

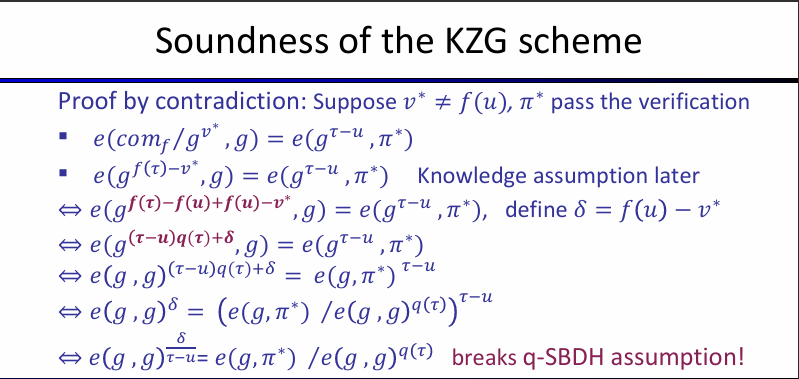

q-Strong Bilinear Diffie-Hellman

The q-Strong Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (q-SBDH) assumption is, given $(p, \mathbb{G}, g, \mathbb{G}_T, e), gp = (g, g^\tau, g^{\tau^2},…,g^{\tau})$, it is computationally hard to compute $e(g, g)^{\frac{1}{\tau - u}}$ for any $u$.

Remember two properties of KZG ? They are:

- Correctness: If the prover is honest, then the verifier will always accept.

- Soundness: How likely is a fake proof to be verified?

We can see proof of soundness in the lecture:

Knowledge of Exponent (KoE)

How we can assume the prover knows $f$ such that $comm_f = g^{f(\tau)}$ ? Here is how:

- $gp = (g, g^\tau, g^{\tau^2},…,g^{\tau})$

- Sample some random $\alpha$ and compute $gp^\alpha = (g^\alpha, g^{\alpha \tau}, g^{\alpha \tau^2},…,g^{\alpha \tau^d})$

- Compute two commitments instead of one, $comm_f = g^{f(\tau)}$ and $comm_f’ = g^{\alpha f(\tau)}$

With bilinear pairing, if $e(comm_f, g^\alpha) = e(comm_f’, g)$ there exists an extractor $E$ that extracts $f$ such that $comm_f = g^{f(\tau)}$. This extractor will extract $f$ in our proof above, where we assumed the prover knows $f$.

So, let’s describe KZG with knowledge soundness:

- Keygen: $gp$ include both $(g, g^\tau, g^{\tau^2},…,g^{\tau})$ and $(g^\alpha, g^{\alpha \tau}, g^{\alpha \tau^2},…,g^{\alpha \tau^d})$

- Commit: $comm_f = g^{f(\tau)}, comm_f’ = g^{\alpha f(\tau)}$

- Verify: checks $e(comm_f, g^\alpha) = e(comm_f’, g)$

- Knowledge soundness proof: Extract $f$ in the first step by the KoE assumption.

Generic group model (GGM)

In informal definition, adversary is only give an oracle to compute the group operation, like given $(g, g^\tau, g^{\tau^2},…,g^{\tau^d})$, adversary can only compute their linear combinations.

GGM can replace the KoE assumption and reduce the commitment size in KZG.

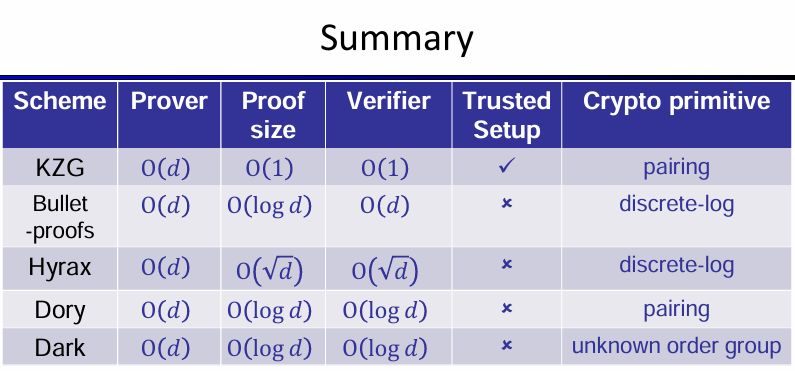

Property of the KZG poly-commit

- Keygen: trusted setup!

- Commit: $\mathcal{O}(d)$ group exponentiations, $\mathcal{O}(1)$ commitment size

- Eval: $\mathcal{O}(d)$ group exponentiations, and quotient $q(x)$ can be computed efficiently in linear time

- Proof size: $\mathcal{O}(1)$, 1 group element

- Verifier time: $\mathcal{O}(1)$, 1 pairing

Ceremony

To relax the trusted setup in practice, there is a process called ceremony. The goal of ceremony is to have a distributed generation of the global parameters so that no one can reconstruct the trapdoor if at least one of the participants is honest and discards their secrets. Here is how to do it:

- Suppose your global parameters are $gp = (g^{\tau}, g^{\tau^2},…,g^{\tau^d}) = (g_1, g_2, …, g_d)$

- As a participant in this ceremony, you sample random $s$ and update $gp’ = (g_1’, g_2’, …, g_d’) = (g_1^s, g_2^{s^2},…,g_d^{s^d}) = (g^{\tau s}, g^{(\tau s)^2}, …,g^{(\tau s)^d})$ with secret $\tau s$

- Check the correntness of $gp'$

- The contributor knows $s$ such that $g_1’ = (g_1)^s$

- $gp’$ consists of consecutive powers $e(g_i’, g_1’) = e(g_{i+1}’, g)$ and $g_1’ \ne 1$ To know more, check Nikolaenko-Ragsdale-Bonneau-Boneh'22.

Variants of KZG poly-commit

Multivariate poly-commit

This was described first in Papamanthou-Shi-Tamassia'13. In this paper, they explains a way to use KZG for multivariate polynomial. The key idea is: $$f(x_1, …, x_k) - f(u_1, …, u_k) = \sum_{i=1}^k(x_i - u_i)q_i(\overrightarrow{x})$$

We have these properties:

- Keygen: sample $\tau_1, \tau_2,…,\tau_k$, compute $gp$ as $g$ raised to all possible monomials of $\tau_1, \tau_2,…,\tau_k$

- Commit: $comm_f = g^{f(\tau_1, \tau_2,…,\tau_k)}$

- Eval: compute $\pi_i = g^{q_i(\overrightarrow{x})}$

- Verify: $e(comm_f/g^v, g) = \prod_{i=1}^ke(g^{\tau_i - u_i}, \pi_i)$

Achieving zero-knowledge

Plain KZG is not zero-knowledge, e.g. $comm_f = g^{f(\tau)} is deterministic. Also remember that to formally show zero-knowledgeness, we need a simulator construction that can simulate the view of the commitment scheme.

ZGKPP'18 shows a method to do this by masking with randomizers.

- Commit: $comm_f = g^{f(\tau) + r \eta}$

- Eval: $f(x) + ry - f(u) = (x - u)(q(x) + r’y) + y(r - r’(x - u))$, and the proof will be $\pi = g^{q(\tau) + r’\eta}, g^{r - r’(\tau - u)}$.

Batch opening: single polynomial

Prover wants to prove $f$ at $u_1,…,u_m$ for $m < d$. The key idea is:

- Extrapolate $f(u_1), f(u_2),…,f(u_m)$ to obtain $h(x)$.

- Find a quotient polynomial from $f(x) - h(x) = \prod _{i=1}^m(x-u_i)q(x)$

- The proof then becomes $\pi = g^{q(\tau)}$

- Now, the verifier will check $e(comm_f/g^{h(\tau)}, g) = e(g^{\prod _{i=1}^m(x-u_i)}, \pi)$

Batch opening: multiple polynomials

Prover wants to prove $f_i(u_{i, j}) = v_{i, j}$ for $i \in [n], j \in [m]$. The key idea is:

- Extrapolate $f_i(u_1), …, f_i(u_m)$ to get $h_i(x)$ for $i \in [n]$

- Find quotient polynomials from $f_i(x) - h_i(x) = \prod_{i=1}^m(x - u_m)q_i(x)$

- Combine all $q_i(x)$ via a random linear combination.

Polynomial commitments based on discrete logarithm

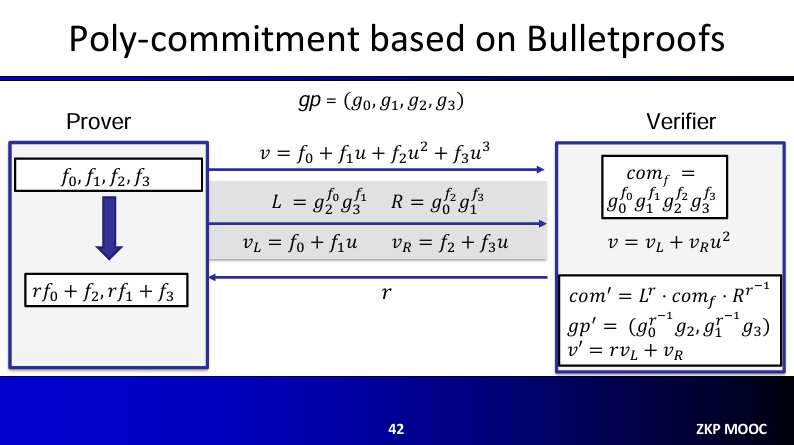

Bulletproofs

Although KZG polynomial commitment is very effective, but require trusted setup is still a problem to solve. Bulletproofs[BCCGP'16], [BBBPWM'18] is one of proof schemes without trusted setup.

$keygen$: Bulletproofs have a transparent setup, which sample random $gp = (g_0, g_1, …, g_d)$ in $\mathbb{G}$ $commit(gp, f) \to comm_f$: Suppose you want to commit $f(x) = f_0 + f_1x + f_2x^2 + … + f_dx^d$, then your commitment will be $comm_f = g_0^{f_0}g_1^{f_1}g_2^{f_2}…g_d^{f_d}. Notice that this is a “vector commitment” version of a Pedersen Commitment $eval(gp, f, u)$:

- Find $v = f(u)$

- Compute $L, R, v_L, v_R$, where $L, R$ are commitments of left half and right half of polynomial.

- Receive a random $r$ from verifier and reduce $f$ to $f’$ of degree $d/2$

- Upgrade the bases $gp’$ $verify(gp, comm_f, u, v, \pi)$:

- Check $v = v_L + v_R * u^{d/2}

- Generate $r$ randomly

- Update $comm’ = L^r * comm_f * R^{r^{-1}}$ (magic trick)

- Update the global parameter to be $gp'$

- Set $v’ = rv_L + r_R$ Note that we do $eval$ and $verify$ recursively around $\log d$ times. The idea of Bulletproofs is to recursively divide a polynomial in two polynomials, and commit to those smaller polynomials.

Properties of Bulletproofs

- Keygen: $\mathcal{O}(d)$, transparent setup

- Commit: $\mathcal{O}(d)$ group exponentiations, $\mathcal{O}(1)$ commitment size

- Eval: $\mathcal{O}(d)$ group exponentiations (non-interactive via Fiat-Shamir)

- Proof size: $\mathcal{O}(\log d)$

- Verifier time: $\mathcal{O}(d)$

Other protocols

Hyrax Wahby-Tzialla-Shelat-Thaler-Walfish'18

Improves the verifier time to $\mathcal{O}(\sqrt{d})$ by representing the coefficients as a 2-D matrix.

Proof size: $\mathcal{O}(\sqrt{d})$.

Dory Lee'21

Improving verifier time to $\mathcal{O}(\log d)$.

The key idea is delegating the structured verifier computation to the prover using inner pairing product arguments [BMMTV'21].

Also improves the prover time to $\mathcal{O}(\sqrt{d})$ exponentiations plus $\mathcal{O}(d)$ field operations.

Dark Bünz-Fisch-Szepieniec'20

Achieves $\mathcal{O}(\log d)$ proof size and verifier time

Group of unknown order

Summary