Zero Knowledge Proof: An Introduction

Table of Contents

At the first time I have heard about Zero Knowledge Proof, I felt like it’s totally different about all cryptography knowledge that i learned, so I decided to learn it! In this post, I will try to explain what Zero Knowledge Proof is, with some examples.

I will follow the syllabus which was given at here. You will need to read some papers they suggested.

Resources

[1] [Goldwasser-Micali-Rackoff’89] Knowledge Complexity of Interactive Proof Systems

[2] [Bellare-Goldreich’92] On Defining Proofs of Knowledge

[3] Lecture 3: Interactive Proofs and Zero-Knowledge

Detail

Interactive Proof

Informally, the goal of proof is to convince someone that the certain statement is true.

Euler proved that “There are infinity primes of the form $4k + 3$” by assumming opposite, then lead to contradition

To prove that “I know a factor $p < N$ of number $N$”, you can give anyone $p$ and $N$, and let them calculate $k = N / p$. If $k$ is an integer, then they know that your statement is true

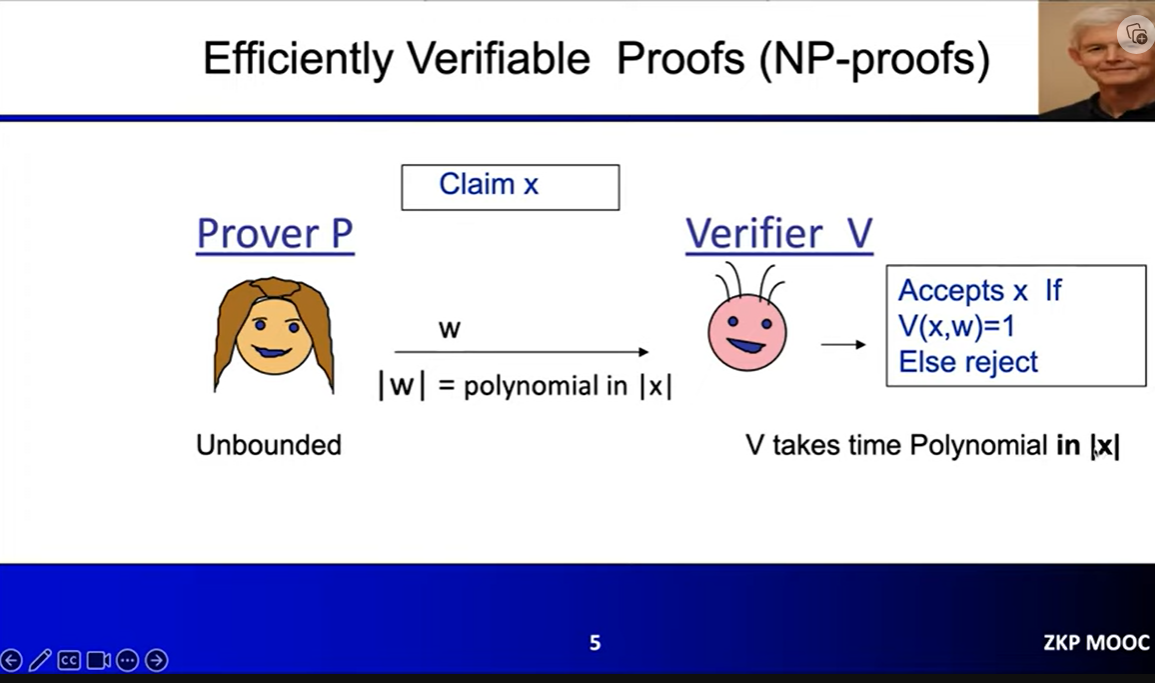

Now, we will talk about another way to describe a proof. We are going to think of proof as an interactive process, with prover and verifier. The prover will prove that the statement is true, and the verifier will check the statement is true or false. This is called Interactive Proof

To define what is Interactive Proof, we need to define some terminology:

Languages: A language is simply a set of strings $L \subseteq \lbrace 0, 1 \rbrace^*$

Statement: A statement consists a tuple $(x, L)$ or more intuitively, $x \in L$

Interactive Proof System:

An interactive proof system for a language $L$ is a protocol between two algorithms: a (possibly unbounded) prover $P$ and an efficient (probabilistic polynomial time) verifier $V$

At the start of the protocol, both the prover $P$ and the verifier $V$ are given some instance $x$. At the end of the protocol, the verifier $V$ either accepts (it is convinced that $x \in L$) or rejects (it is not convinced that $x \in L$)

For a proof system to be useful, it must satisfy the following two properties:

Completeness: If $x \in L$, then an honest prover $P$ that just follows protocol specification should be able to convince $V$

Soundness: If $x \notin L$, then no prover $P$ (that can possibly cheat by deviating from the protocol specification) should not be able to convince $V$

Now we will use definition in [1]

Definition 1.1(Interactive Proofs). Let $L$ be any language. Let $\braket{P, V}$ be a protocol specification between a prover $V$ and the verifier $V$. Then we say that $(V, \braket{P, V})$ is an interactive proof system for $L$ if the following two properties are satisfied:

- Completeness: $\forall x \in L$,

$$ Pr[\braket{P, V}(x) = 1] = 1 - \epsilon $$

- Soundness: $\forall x \notin L$,

$$ Pr[\braket{P, V}(x) = 1] = \epsilon $$

where $\epsilon$ is negligible

Zero-Knowledge

Now, we want to prove a statement $x \in L$ without revealing anything else about $x$ other than the fact that $x \in L$. For a language $L$, we have two parties:

An honest prover $P$ with input $(x, w)$ such that $w$ is an $L$ witness of $x$. It follows the protocol specification exactly

A dishonest verifier $V^*$ with input $x$. It can deviate from the protocol specification.

The goal of the verifier $V^*$ is to infer some information about x from its interaction with $P$

In other words, the verifier is given (i) all the transcript $(q_1,a_1,…q_j,a_j)$ and (ii) the internal coins (randomness) it used $(r_1,…,r_j)$ throughout the protocol. Then, it tries to learn additional information about $x$. Then, we define the view of $V^*$ as the random variable

$$ \mathsf{view}_{V^*}(P, V^*)[x] = \braket{q_1,a_1,r_1,…,q_j,a_j,r_j} $$

Then, our goal is to require that no adversary can gain any additional “knowledge” about $x$ from $\mathsf{view}_{V^*}(P, V^*)[x]$

Knowledge. In cryptography, “knowledge” defined with respect to things that you can compute efficiently

Given $N = p * q$ and $p$, we will have “knowledge” of $q$ by calculate $N / p$

Given $h = \mathsf{SHA256}(m)$, we won’t have “knowledge” of $m$ because we can’t calculate $m$

Zero-Knowledge. We say that a protocol is zero-knowledge if any information that a verifier could have derived from the transcript of the protocol, could have orginally been computed efficiently just from $x$ (without any transcript)

Definition 1.2(Zero-Knowledge Proof). Let $L \in NP$. Let $\braket{P, V, }$ be a protocol specification between a (possibly unbounded) prover $P$ and a (PPT) verifier $V$. Then, we say that $\braket{P, V}$ is an interactive proof system for $L$ if the following properties are satisfied

- Completeness: $\forall x \in L$,

$$ Pr[\braket{P, V}(x) = 1] = 1 - \epsilon $$

- Soundness: $\forall x \notin L$,

$$ Pr[\braket{P, V}(x) = 1] = \epsilon $$

where $\epsilon$ is very small

- (computational) Zero-Knowledge: $\forall V^*$, $\exist (PPT) \ \mathsf{Sim}_{V^*}$ such that $\forall x \in L$

$$ \mathsf{View}[\braket{P(x, w) \leftrightarrow V^*(x)}] \approx \mathsf{Sim}_{V^*}(x) $$

Example:

Understanding Zero-knowledge proofs through illustrated examples

Do all NP languages have Zero Knowledge Interactive Proof ?

Short answer: Yes

Theorem 1.1[GMW86, Naor]: If one-way functions exist, then every language $L$ in $\mathsf{NP}$ has computational zero knowledge interactive proofs

Idea of the proofs:

[GMW87] Show that an NP-Complete Problem has a ZK Interactive Proof if bit commitments exist

[Naor] One Way functions $\to$ bit commitments protocol exist

Definition 1.3(Commitment). An efficiently computable function $\mathsf{Comm}: \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{R} \to \mathcal{C}$ is a (perfectly) binding commitment if it satisfies the following two properties:

- Hiding: For all $m_0, m_1 \in \mathcal{M}$

$$ \lbrace \mathsf{Comm}(m_0, r): r \xleftarrow{\mathcal{R}} \mathcal{R} \rbrace \approx_c \lbrace \mathsf{Comm}(m_1, r): r \xleftarrow{\mathcal{R}} \mathcal{R} \rbrace $$

- Binding: For all $m_0, m_1 \in \mathcal{M}$, $r_0, r_1 \in \mathcal{R}$, if $m_0 \ne m_1$:

$$ \mathsf{Comm}(m_0, r_0) \ne \mathsf{Comm}(m_1, r_1) $$

We can think of a commitment as an envelope that you can’t see inside, but binds you to a value

Example: [3] 3.2

Application

Can prove relationships between $m_1$ and $m_2$ never revealing either one, only $\mathsf{Comm}(m_1)$ and $\mathsf{Comm}(m_2)$.

Examples: $m_1 = m_2, m_1 \ne m_2$ or more generally $v = f(m_1, m_2)$ for any poly-time $f$

Generally: A tool to enforce honest behavior in protocols without revealing any information. Idea: protocol players sends along with each next-msg, a ZK proof that next-msg = Protocol(history h, randomness r) on history h & c = commit(r)

Possible since $L = \lbrace \forall r | (next, msg) = Protocol(h, r)$ and $c = \mathsf{Comm}(r) \rbrace$ in NP.

About Arthur-Merlin protocol:

- Arthur-Merlin protocol is an interactive proof system in which the verifier’s coin tosses are constrained to be public, mean that prover knows the coin too

- The question is, is coin privacy necessary ?

Theorem 1.2(Goldwasser-Sipper): AM = IP

- In practice, AM protocol can remove the interaction part by using Fiat-Shamir Heuristic

Warning: this does NOT mean every interactive ZK proof can transform to AM protocols and then use Fiat-Shamir heuristic, since IP = AM transformation requires extra super-polynomial powers from Merlin, and for Fiat-Shamir heuristic to work, Prover must be computationally bounded so not to be able to invert H. Yet, many specific protocols, can benefit from this heuristic